Ryders on the Storm: Celebrating the Art of Albert Pinkham Ryder

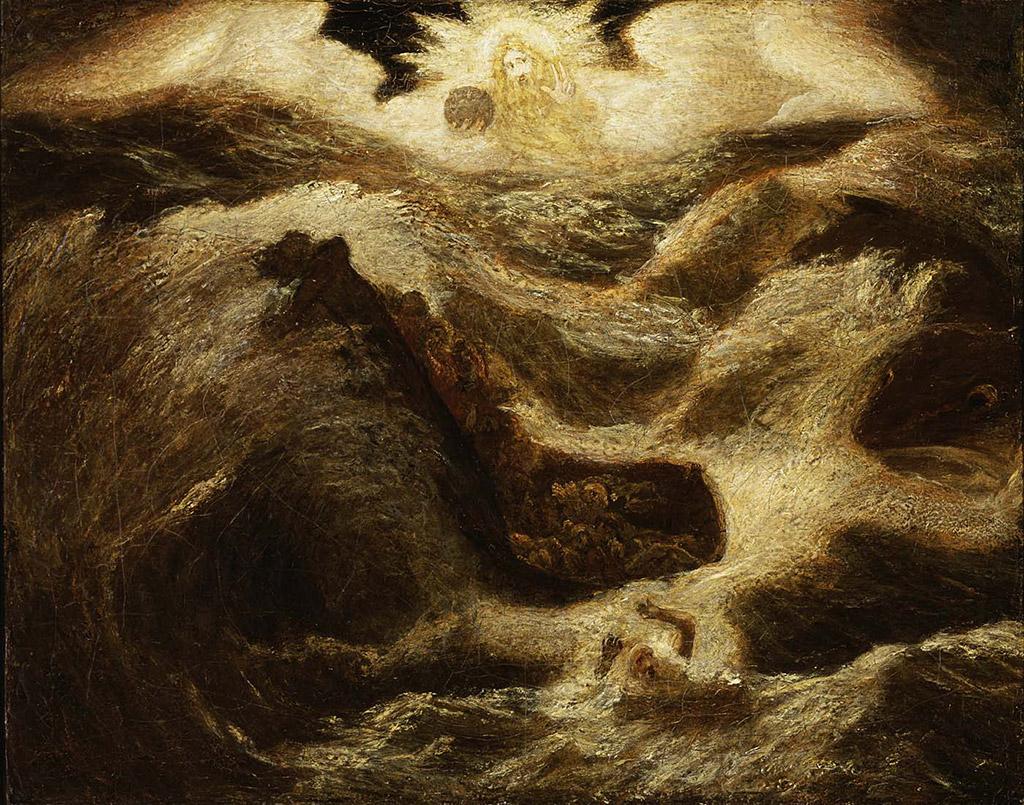

Before Betsy Broun retired from the helm of the Smithsonian American Art Museum last fall, she gave a talk where she revealed her top ten works (ok, seventeen works) of art in the collection, beginning with Albert Pinkham Ryder’s Jonah. Ryder, who died one hundred years ago today, was an artist close to Broun’s heart and the subject of a book she published in 1989.

“I worry that he’s in danger of being forgotten,” she told us while sharing her thoughts about his work, his era, and his influence on the next generation of artists. According to Broun, the difficult later years of Ryder’s life—depression, ill health, loneliness—can be seen in Jonah, as the hero struggles in the churning sea for dear life. He was 70 years old and had been declining since a hospitalization in 1915; the cause of death was basically kidney failure.

Despite the difficulties, when he died, Ryder was already lionized as an icon of American art. According to Broun, “There was an entire room dedicated to his work at the famous Armory Show of 1913 where his art was offered as a precursor to modernism. In 1918, the Metropolitan Museum of Art did a memorial exhibition with 48 paintings. Ryder’s deep involvement with the properties of oil paint and the painting process, and his intuitive powerful approach to composition, led such modernists as Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, Jackson Pollock, and many others to view him as the key inspiration for a new modern style, despite his fondness for historical, Shakespearean, and Biblical subjects.”

What makes Ryder’s legacy a bit fuzzy is that even before he died, suspicious paintings were starting to circulate, and, as Broun tells us, “the first Ryder biography (by Frederic Fairchild Sherman in 1920) was inaccurate, full of romantic made-up legends, and illustrated with several forgeries. By 1932, there were literally hundreds of ‘wrong’ works clouding the market and making Ryder a difficult artist for scholars, collectors, and museums to study and collect. Art historian and former director of the Whitney, Lloyd Goodrich, led the way in using new lab techniques such as x-radiography to sort out the originals from the fakes.”

SAAM has the most important collection of Ryders in the world, including a gallery on the second floor featuring nine of his visionary works, including Jonah. In this dramatic, psychologically-charged, life-or-death seascape, the artist fashioned a god of light spreading his wings, exhibiting what Broun called “a spiritual tenaciousness.”